Ford E-Transit review: Opening up new routes

Electric vans are only suitable for inner-city deliveries. Too little range, too little payload, at least, that is the general credo. Our drive review will show whether the Ford E-Transit can dispel this prejudice and stand for a new generation of zero-emission vans.

After small panel vans and high-roof station wagons, electrification is also increasingly taking place in vans in the transporter segment, symbolised by the Mercedes eSprinter. Electric vans currently available, more than adequately serve inner-city delivery applications, such as the Courier, Express, & Parcel (CEP) industry. At the same time, the electric freight carrier must have a sufficiently large battery and more payload if it is going to get beyond inner-city areas to cover even more routes and reach more customers.

While competitors already offer zero-emission versions in their class, the Ford E-Transit appeared relatively late and has overtaken the class from behind. Now that the Ford E-Transit vans have been on the market in the USA, Europe, and the UK for a year, a look at the competition and their specs reveals that the US manufacturer has set a new benchmark. Ford has been paying attention to the other kids in class.

Ford also has an advantage in this sector, because the traditional ICE Ford van has already been one of the most important van models on the market for decades, and the Transit is a familiar model. For example, shortly after Ford announced the electric van, the company received more than 5,000 blind orders.

* * *

Ford sets new range banchmark

There is no question that many electric vans currently suffice the range requirements for urban logistics. Since StreetScooter pioneered electric vans for inner-city deliveries last decade, electric vehicles have shown they are suitable for inner-city environments. The StreetScooter spec is precisely tailored to the CEP sector, or in this case, Deutsche Post DHL. With its range of up to 158 kilometres according to WLTP (combined), the eSprinter also covers some delivery areas beyond the inner city. In the logistics sector, 50 to 70 kilometres per shift are the order of the day in Germany. Beyond the city centre, the eSprinter reaches its limits in cold to wintry temperatures (note, however, that Mercedes plans to present the next eSprinter generation this month). The Renault Master E-Tech offers a slightly longer range of 200 kilometres (WLTP). An Opel Movano-e still manages up to 248 kilometres.

And the Ford E-Transit? With the E-Transit’s maximum range of 317 kilometres, the only van currently on the market offering more range is the Maxus eDeliver 9, which is supposed to go up to 353 kilometres with the largest battery. For our real-life test in Germany, we drove the Transit version 350 L3H2, which has a WLTP range of up to 255 kilometres. Whether 317 or only 255 kilometres, according to WLTP, tradespeople with longer journeys will still (have to) go with diesel.

We found that the E-Transit consumed between 24 and 26 kWh/100 km while driving in an urban environment, up to 30 to 32 kWh/100 km on the motorway, according to the data from the onboard computer and the SoC. This results in practical ranges of up to 280 kilometres for urban driving and around 200 for predominantly motorway driving. If you only drive on the motorway at speeds well above 100 km/h, you should expect a range of around 150 kilometres.

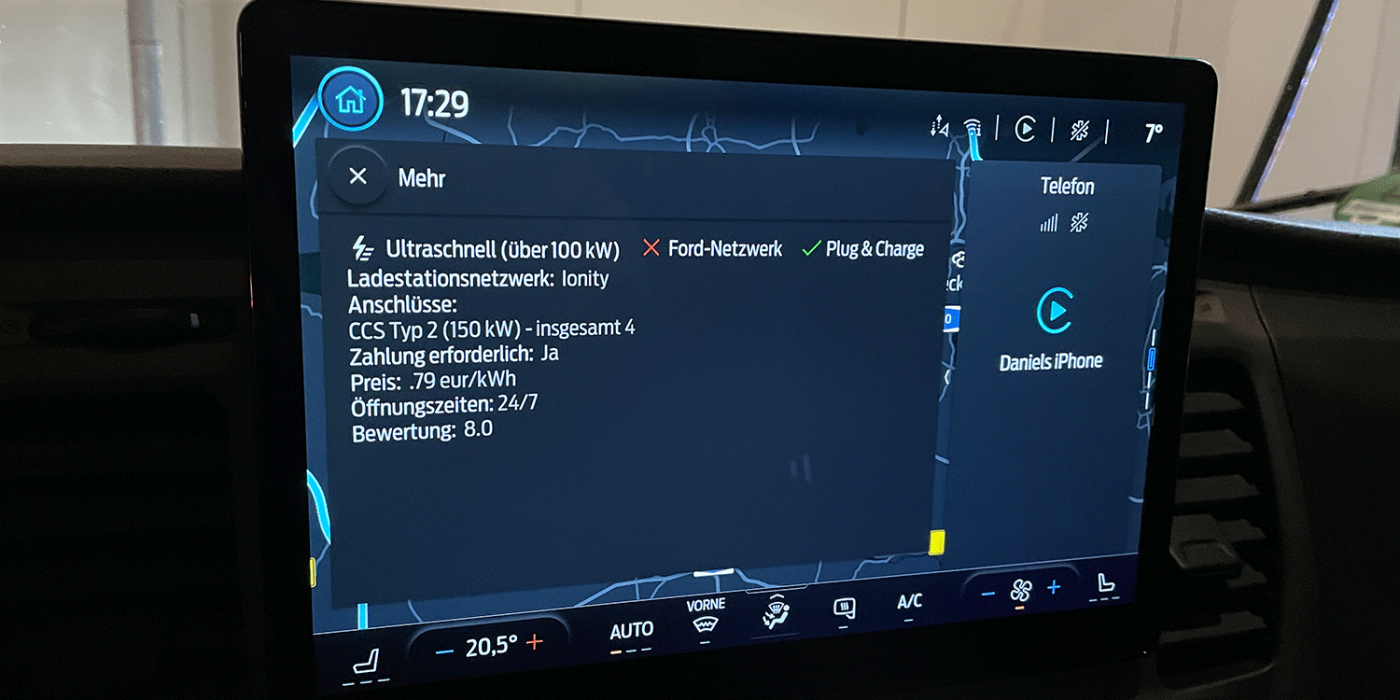

This range is made possible by a 68 kWh battery (net). Compared to other manufacturers, Ford only offers one battery size. If the battery is empty, it can be recharged in just over eight hours at an AC charging station. Ford says a maximum charging power of 11 kW (three-phase) is sufficient. The faster charging solution is, of course, DC charging – most often provided by publicly accessible fast-charging stations. Here, with a maximum charging power of 115 kW, the battery can be charged from 15 to 80 per cent within 35 minutes. This charging process works well even in cold temperatures – our experience has shown that even a short drive on the motorway is enough to bring the battery up to temperature. For a charging test, we drove around 20 kilometres on the motorway at 7 degrees and with a cold battery to arrive at the fast charger with a 15 per cent State of Charge (SoC). After just over a minute at the High Power Charger, the charging station only displayed a charging power of 105 kW. Still, the display in the vehicle nevertheless promised a charge level of 80 per cent after around 40 minutes – and it delivered as promised.

If public charging is required, the navigation system helps to find a charging station. When the car first hit the market in the spring of 2022, there was no route planning with automatic charging stops, and this useful function has since been integrated. Random checks showed that the charging stops were well-planned. For example, the system planned three charging stops for a distance of just under 400 kilometres (almost exclusively on the motorway). The navigation indicates the SoC (state of charge) on arrival at the charging point and from which the journey can be continued. On the route in question, this resulted in a journey time of a good 6.5 hours, including a charging time of 1:45 hours in total. Even if the relevance of such a function is currently rather limited for vans, Ford distinguishes itself from the competition here as this kind of planning is not standard with other models.

In such a large van, the positioning of the charging port is even more important than in a passenger car. The E-Transit’s charging port is located at the front of the vehicle. During our test drive, we discovered a disadvantage which was not least due to the length of the van: At various hardware or DIY stores, the combination of charging point placement and parking space conditions meant that charging was either not possible at all or only with very large obstacles. In the test, for example, the car had to be parked so that it was only possible to exit via the passenger side. This is where it is crucial to plan to charge infrastructure not only for electric cars but also for electric vans for commercial vehicles for tradespeople.

The E-Transit can also deliver electricity off-grid. For example, there are two household sockets near the tailgate, each of which can provide a maximum power of 2.3 kW. A novelty among electric transporters.

Two motors provide more power than diesel engines.

Ford offers two motor options for the E-Transit: customers can choose between a motor with an output of 135 kW – like the variant we tested – and one with 198 kW. But even the smallest electric motor offers more power than the largest diesel engine for the Transit. The Mercedes eSprinter only manages 85 kW, and the Stellantis models up to 90 kW. While up to 120 km/h is possible with the eSprinter, at least as an option, the Stellantis vans can only manage a maximum of 100 km/h. Ford’s models – albeit only the 3.5-tonne version – have a maximum speed of 130 km/h. Due to its classification as an N2 commercial vehicle, the 4.25-tonne version is legally only allowed to drive at a maximum of 90 km/h in Germany.

While the competitors rely on front-wheel drive, Ford has opted for a rear-wheel drive with a specially adapted rear axle and independent suspension. Compared to the competition, this decision makes for a noticeably more comfortable driving experience, as we found out. For us, driving the E-Transit felt much more like driving a car with excellent handling. Even at top speed, the E-Transit cut a good figure. What should also not go unmentioned is that when the battery is low, like an SoC of about 16 per cent, the top speed is throttled back. The motor power decreases noticeably, and it is difficult to get still close to the 115 km/h limit. On the motorway, this can be annoying. However, this plays a subordinate role in the city and country roads.

A packhorse among the E-transporters

Ford offers the E-Transit as a classic panel van with a double cab and also as a flatbed for various bodies. Customers can choose between lengths L2 to L4 and heights H2 to H3. Depending on the version, the load compartment volume can range from 7.2 to 15.1 cubic metres. In total, there are 25 variants to choose from.

E-Transit stands out from the competition when it comes to the payload. Alongside the range, this is not an entirely unimportant criterion. The payload possibilities for the E-Transit are quite broad, ranging between 795 kg (L4H3) and a maximum of 1,685 kg (L3H2). The latter variant has a permissible gross weight of 4.25 tonnes and theoretically could no longer be driven with a Class B driving licence. In Germany, for example, commercial vehicles with an alternative drive in class N2 with a maximum permissible gross weight of up to 4.25 tonnes can be driven with a passenger car driving licence if one has had it for at least two years, and a general increase is planned.

How do the competitors fare? The eSprinter has a maximum load of 848 kg, the Renault Master E-Tech can carry up to 1,050 kg, the Stellantis models up to 1,110 kg, and the Maxus eDeliver 9 has a maximum load of 1,275 kg. Only the Fiat E-Ducato trumps the Ford E-Transit with a payload of 1,910 kg.

In terms of towing capacity, in some variants, Ford’s E-Transit has a towing capacity of 750 kg, while other variants cannot tow a trailer.

There is also variety in the range of assistance systems. Compared to their diesel counterparts, the individual equipment variants offer a higher level of standard equipment, even in the basic version. A nice detail was that the LED spotlight at the rear has enough radiant power to provide sufficient light on dark winter evenings.

Ford E-Transit test conclusion

As good as all this may sound, at the end of the day, all this data and these features come at a price. In Germany, for example, although the price starts at 59,890 euros (net), our test variant was priced at 60,490 euros. A Movano-e starts at 59,990 euros, while an eSprinter starts at 62,001 euros. A Maxus eDeliver 9 with a comparable battery size starts at 64,490 euros. Only the Fiat E-Ducato is even more expensive, with a base price of 73,250 euros (DC charging another 2,500 euros more). The bare truth of the matter is that even though a comparable diesel Transit (in terms of engine power and payload) is almost 10,000 euros cheaper.

After deducting the government subsidy in, for example, Germany (environmental bonus), the difference may be reduced – noting, of course, that a number of European countries have subsidies for electric vehicles, and some subsidise the difference to a conventional vehicle by 40 to 80 per cent. Also advantageous are low operating costs during the vehicle’s lifetime – electric vehicles generally have fewer moving parts and, accordingly, much lower maintenance requirements – and, therefore lower costs. Added to this is the better equipment, such as the E-Transit’s ability to function as an on-site power source.

Fleet managers have to calculate precisely and consider the charging time in terms of possible time on the road. For shorter distances, there might be one great case for overnight charging and for longer distances, a worse case with a total of almost two hours of DC charging per 400 kilometres.

Reporting by Daniel Bönnighausen, Germany.

0 Comments