What Europe can learn from Chile’s rapid shift to electric public transport

The Agora Verkehrswende think tank seeks the answer to this question, and has taken a closer look at the development in Chile, analysing the transport transformation along with the political and public will that made it happen in detail. Head researcher Linda Cáceres Leal found that, alongside subsidies and public interest, reliability plays a major role in the sustainable transformation.

Chile has long prepared for electric vehicles, while also considering key background factors, such as energy and infrastructure. It all started with Chile’s first ‘Nationally Determined Contribution’ (NDC) in 2015 and the ‘2050 Energy Policy’ in 2016, which explicitly incorporated transport transformation into their mandates, including the pioneering ‘National Electromobility Strategy’ (2017) that set a 40 per cent EV adoption target for private vehicles and 100 per cent for public transport by 2050.

After 2020, Chile accelerated its electrification efforts: In 2021, a fuel efficiency law was introduced for imported vehicles, which affects virtually all vehicles in the country, given Chile’s nascent vehicle industry. By 2022, this was updated to include all light and medium vehicles, as well as all public transport vehicles, such as taxis, that would need to be zero-emission by 2035.

By then, Chile’s success had also drawn international attention: Chile’s long-term low emission development strategies (LT-LEDS) were ranked among the world’s best by the World Resources Institute in 2023, outperforming even the EU and UK in policy coherence. This study also concluded that while transport requires a large investment, it also offers the highest return in the energy sector, representing 50 per cent of Chile’s carbon neutrality targets.

The study outlines five key takeaways from its research:

- Long-term climate commitment and policy consistency across political cycles are fundamental for transport decarbonisation

- Innovative policy and financing tools are essential in emerging markets for attracting investment and creating certainty

- Scaling charging infrastructure and fleet renewals with electric vehicles to secondary cities are critical for full transport decarbonisation

- Electrification must now expand beyond buses to meet full decarbonisation targets

- High-visibility electric transport projects create momentum for other countries to transition

Looking at the industry and political uncertainty plaguing Europe and the US today, the first point is logical: Only if manufacturers can rely on contracts being upheld and requirements staying in place can they plan their own decarbonisation efforts. Chile’s success, as the study states, is due to the long-term planning. The political and financial decarbonisation efforts in Chile included ‘early financial mechanisms like Law No. 20.378 in 2009, pilot deployments between 2016 and 2020, and later-stage mandates such as the 100 per cent Zero Emission Vehicle (ZEV) procurement target by 2035.’ Considering the rate at which EU debates on the subject are progressing, there is certainly something to learn.

Making the transport system attractive for investment poses another challenge to electrification efforts. Santiago runs on a business model that separates asset ownership from operations, nudged along by subsidies, which ‘significantly reduced investor uncertainty,’ according to the study’s authors. Furthermore, the combination of energy tariff reforms, which save operators up to 22% of costs, with fuel economy standards, which penalise the use of polluting energy sources, makes it clear in which direction investment will be more profitable.

The third point on the list shows one major weakness of the Chilean model: “While the capital accounts for 95 per cent of Chile’s operational electric buses and 28 of its 30 charging terminals, 86 per cent of EVs and 75 per cent of public charging infrastructure, regional cities face significant infrastructure gaps.” Public transport and infrastructure can be difficult to implement in rural areas, where distances are larger, while passenger numbers are lower.

Regarding the fourth point, the study’s researchers point out that public transport is only part of the mobility ecosystem in any country. Particularly, the ‘slow adoption of electric freight and private vehicles, with a mere 2.5 per cent penetration, risks stalling sector-wide progress.’

The study’s author, Linda Cáceres Leal, further explained: “Electrification plays a major role in climate commitments, but technological change by itself will not solve problems such as congestion, nor will it reduce emissions if people continue relying primarily on private cars. Micromobility (bike-sharing, e-bikes, scooters, etc.) becomes a natural complement to public transport because it enables first- and last-mile connectivity and makes transit more attractive and convenient. In Chile, we have seen elements of this integration, but only partially.”

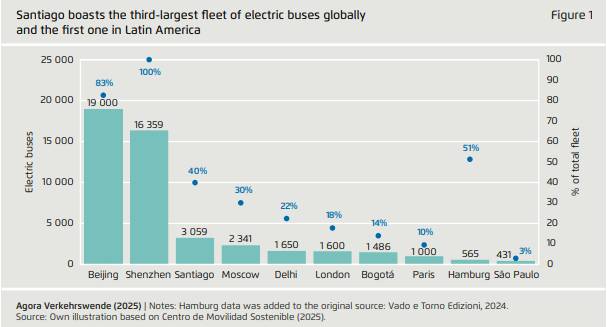

Finally, the authors of the study assert that making such decarbonisation projects more high-profile creates momentum for other countries to undertake their own transport electrification initiatives. “This success has inspired similar transport transformations across Latin America, showcasing the ripple effect of targeted public investments,” the author stated.

According to the study’s long-term analysis of Chile’s electric vehicle transformation, “Chile‘s layered policy approach, which combines a longterm strategy with financial mechanisms such as differential electricity tariffs and subsidies, together with regulatory certainty provided by efficiency standards and binding targets, has driven measurable progress.” The authors admit that this has not spread as quickly to other vehicle segments, however, ‘their foundational policies suggest similar growth trajectories,’ should the commitment be sustained.

Interestingly, the author specified that the lack of a local industry helped the transition along: “Chile’s lack of a domestic automotive industry actually made its transition easier, because it did not face the resistance or industrial restructuring challenges that countries like Germany are experiencing. The country could adopt new technologies without having to protect incumbent manufacturers.”

Further fields of electrification

Freight transport is one such area, which “remains primarily in a pilot phase focused on data collection.” Currently, there are about 280 electric trucks on the roads in Chile, which have provided valuable metrics, showing, for example, that operating costs can be reduced by 70 per cent on average. A total of 6.2 tonnes of emissions were saved during the testing phase here, which collected data from 15 vehicles.

The authors behind the study believe that Chile represents a good case study, and the success can be replicated elsewhere: “Chile’s trajectory is particularly instructive in demonstrating how policy can advance the transport transition in an emerging economy. For Europe, and particularly for Germany, understanding this case offers crucial insights into electrification enablers and outlines opportunities for transcontinental cooperation that would accelerate the global shift.”

Electrification of the public transport system, despite making up 40 per cent of emissions across Latin America, remains only part of the equation, as the study’s initiators further added: “Key elements such as public transport coverage expansion, modal shift incentives (for example, cycling infrastructure or pedestrianisation) and urban planning reforms were beyond the scope of this study, though they remain critical for achieving Chile’s broader emission reduction targets.” Linda Cáceres Leal further elaborated: “The success of the electric bus system in Santiago is closely linked to service improvements, extended route coverage and a renewed sense of ownership among users, which

encouraged people to actually board the buses. Without demand, even the cleanest fleet serves little purpose.”

Outlook for Chile’s e-mobility push

The study does not suggest that the e-mobility transformation is complete, though it has a few suggestions going forward. For example, rural areas should receive more attention, so that Santiago does not completely leave the rest of the country behind in electrification. More attractive policies should be implemented to help the private EV market grow, which currently stands at 2.5 per cent. Tax incentives and battery leasing programmes are cited as examples to help ease this process along.

The author also asserts that charging infrastructure remains an issue in Chile, with only one public charging station per 18,000 residents. This may also explain the low level of interest in private EVs. Here, the study recommends “strategic placement of 150kW+ fast charging stations along major highways, combined with urban mandates for new developments to include charging stations.”

In addition to providing public transport options, the decision to use public transport options over a personal car is also generally more complex, as Cáceres Leal explained: “Latin America faces the same cultural challenge you mention for Europe and the US: the private car is often perceived as a symbol of status, comfort and safety. Encouraging people to leave their cars has been a long-standing debate in the transport sector and there is no single solution, because the reasons people prefer private vehicles are complex and varied. In Europe, where concerns about personal safety on public transport are less prominent than in parts of Latin America, there is more room to appeal to citizens’ environmental awareness and collective responsibility.”

Another interesting aspect to electric bus fleets is energy storage: Cáceres Leal explained that “Bus depots present highly predictable charging patterns, which make them ideal assets for smart-grid management. In the future, large end-of-life bus batteries could serve as stationary storage, providing flexibility services and enhancing grid resilience.”

Transferability to other markets

How these lessons can be applied in other countries is a fairly large question. Some factors depend on how the population is distributed, as well as how the area is geographically structured. A number of factors also contribute to the electrification, including the culture surrounding public transport, as well as the funds committed to acquiring and maintaining an electric vehicle fleet as well as charging it. Political deadlines must also be secured and reliable, as the industry needs stable conditions to orient its production facilities towards.

In Europe, the ACEA recently published its statistical findings, proving that while electric buses are growing, logistics is still far behind. Specifically, Germany is leading the charge in Europe in absolute terms, having acquired 1,202 electric buses last year, showing a growth margin of 108%. This is followed by Sweden (698 units, +684%) and Belgium (+389%). Other strong performers include Romania (455 units, +62%) and Lithuania (143 units, +170%). This means that currently, electric buses hold a 22 per cent market share across Europe, up from 15.9% last year.

Across the globe, there have been further instances of such investment. For example, in October, the state of New York earmarked 80 million USD for emissions-free public transport options, despite a markedly different tone coming from the federal government. India also introduced subsidies for electric buses, and managed to approve nearly 10,000 units after only four months, marking 70 per cent of the total funding pot. In the summer, Scotland also set up a £40 million fund for the procurement of zero-emissions buses, marking the second and last phase of the funding programme ‘ScotZEB2’.

While these funds will likely see a major transformation of local public transport, the policies that enabled them will have to endure for the system to change. As the city of Hull noted, for example, funds for buses are not sufficient, as charging infrastructure and maintenance also play a major role in such major public acquisitions. Political deadlines must also be secured and reliable, as the industry needs stable conditions to plan and adapt its production facilities.

Funds alone are not the deciding factor in electrifying public transport, as Cáceres Leal explains how Santiago de Chile was able to achieve its success: “The

city benefited from a relatively mature regulatory framework, access to private capital, and strong institutional capacity, but many of the tools it used (such as concession redesign, longer contracts for electric fleets, guarantees on battery performance, or blended finance with international partners) can be adapted to different contexts. Not every market can replicate Santiago’s model immediately, but the principles are transferable: reduce uncertainty for operators, stabilise operating costs, and ensure long-term policy consistency.”

Regarding the German market, Linda Cáceres Leal had more specific advice: “Electrifying buses remains an especially sensible strategy because, unlike private cars, they operate intensively and predominantly in dense urban areas where air-quality improvements are most urgently needed. In that sense, the German context should absolutely benefit from a stronger and more stable policy lead, not only to accelerate fleet renewal but also to provide the planning security that operators require.”

agora-verkehrswende.org (study as PDF)

2 Comments