Geotab analysis: measuring the impact fast charging has on the loss of battery capacity

In electric vehicles, degradation refers to the ageing process of the traction battery, which leads to a permanent loss of storage capacity and, consequently, a reduction in range. Today, EV manufacturers typically guarantee that the battery will retain at least 70 per cent of its original capacity after eight years or a maximum of 160,000 kilometres following a full charge. In other words, some degradation is normal, but it usually occurs to a lesser extent than covered by battery warranties; otherwise, manufacturers would constantly have to replace battery modules or even entire battery packs at their own expense. For example, a recent study by P3 demonstrated that EV batteries last significantly longer than previously thought, though it did not analyse charging behaviour in as much detail as Geotab has done.

Geotab, a global provider of telematics services and fleet management solutions based in Canada, has analysed real-world data to determine the impact of charging behaviour on the degradation of traction batteries. Specifically, the study examined whether vehicles are primarily charged slowly using alternating current (AC), for example, at a home wallbox, or whether fast charging with direct current (DC) is preferred. While fast-charging infrastructure has been expanding significantly for some time, a persistent misconception remains that frequently charging batteries at very high power levels—such as 100 kW and above—could be harmful.

Faster degradation than in 2023

For this study, Geotab examined real-world battery condition data from more than 22,700 electric vehicles across 21 brands, drawing on several years of aggregated telematics data. The findings revealed a slight increase in the annual battery degradation rate to 2.3 percent, compared to 1.8 percent in 2023. This means the State of Health (SoH), or remaining capacity, decreases by this amount each year. In practical terms: if a 60 kWh battery degrades to an SoH of 80 percent over time, it will perform like a 48 kWh battery and consequently offer significantly less range than when new.

Geotab attributes the slightly increased battery degradation rate to the growing use of high-power DC fast chargers by EV drivers—but does not consider this development alarming. “EV battery health remains strong, even as vehicles are charged faster and deployed more intensively,” said Charlotte Argue, Senior Manager, Sustainable Mobility at Geotab. “Our latest data shows that batteries are still lasting well beyond the replacement cycles most fleets plan for. What has changed is that charging behavior now plays a much bigger role in how quickly batteries age, giving operators an opportunity to manage long-term risk through smart charging strategies.”

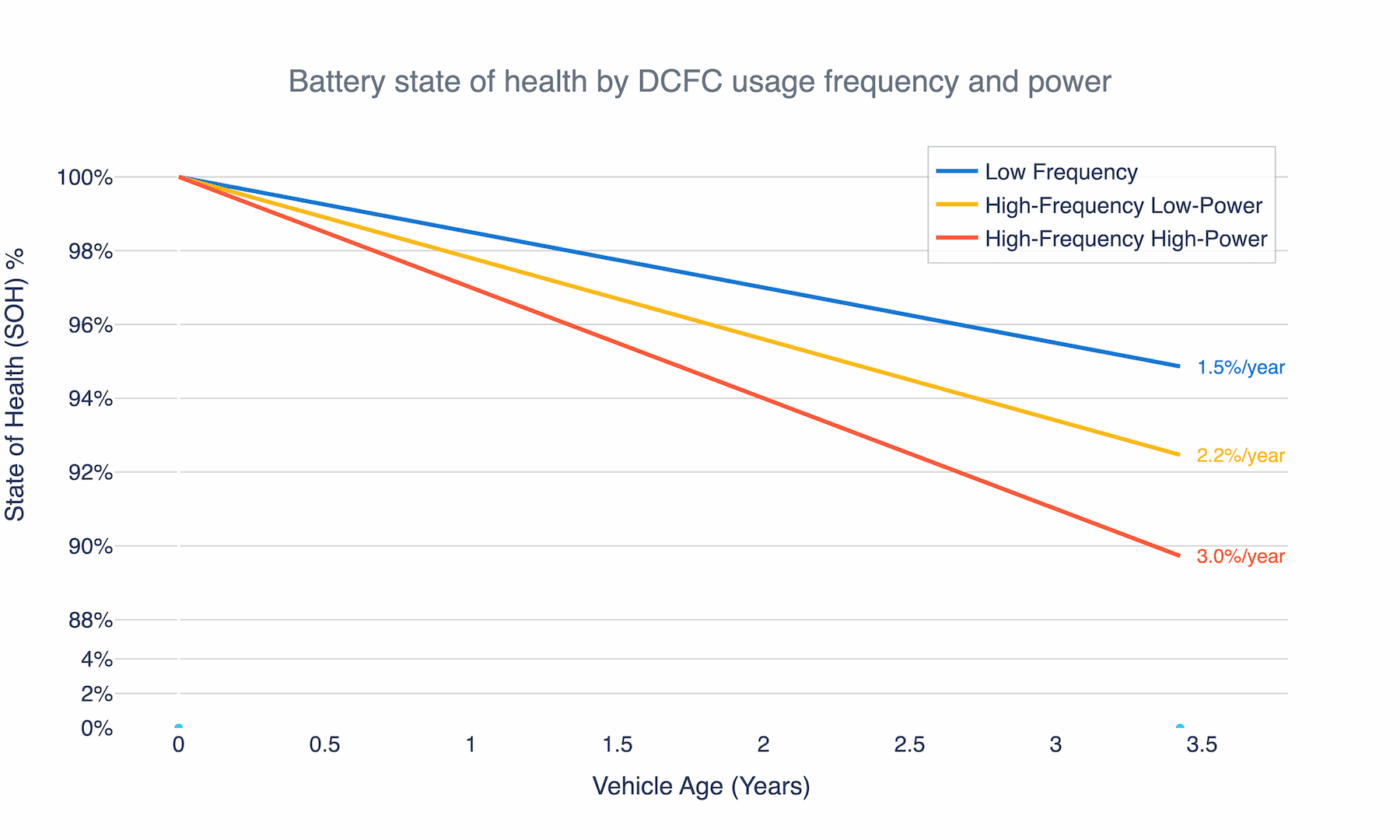

However, the analysis also shows that charging power now has the strongest influence on battery condition and wear. Specifically, EVs that frequently used DC fast charging at power levels above 100 kW exhibited faster degradation, averaging up to 3.0 per cent per year, compared to just 1.5 per cent for vehicles primarily charged with AC or at lower power levels.

Unfortunately, the data does not allow for precise calculations of how many years it would take for batteries to reach a specific SoH. This is because capacity loss does not follow a strictly linear or exponential pattern. Instead, there is often a rapid decline in the first one to two years, before a second phase of slower and more consistent ageing begins. Additionally, charging behaviour can change over time.

Even with HPC preference, SoH remains within warranty limit

When considering the typical eight-year warranty period, it can at least be estimated that the SoH remains above the critical threshold of 70 per cent in all scenarios. Based on the annual degradation rates from the Geotab analysis, it is reasonable to assume that vehicles predominantly charged with AC lose only around 12 per cent of their capacity, those with mixed charging habits lose about 17 per cent, and those frequently using DC fast charging lose up to 22 per cent. In other words, even with frequent DC fast charging, the SoH would still be around 78 per cent, which is above the critical 70 per cent threshold.

“For fleets, the focus should be balance,” Argue added. “Using the lowest charging power that still meets operational needs can make a measurable difference to long-term battery health without limiting vehicle availability.”

Another important factor for remaining capacity is vehicle usage frequency: vehicles used more often show slightly faster degradation, with an annual increase of about 0.8 per cent compared to the least-used group. Other factors, such as climate, had a smaller independent impact. Vehicles operated in hotter regions exhibited about 0.4 per cent faster degradation per year than those in temperate climates.

0 Comments