EVs are getting cleaner faster than expected

There are numerous analyses on the ‘life cycle’ emissions of vehicles, and depending on which factors are included and how they are weighted, results vary slightly. Which emissions are counted towards production? Are the data generalised, or do they capture detailed supply chains for each component, including transport emissions? For petrol and diesel vehicles, are only tailpipe CO2 emissions counted or also those from the extraction, refining, and distribution of the fuel? And what electricity mix is used for charging EVs?

Comparing different life cycle analyses can thus be misleading due to such methodological differences. It is more meaningful to compare studies based on the same methodology but using data from different years. This is exactly what the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) has done in its updated study “Life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions from passenger cars in the European Union”, comparing data from 2021 and 2025.

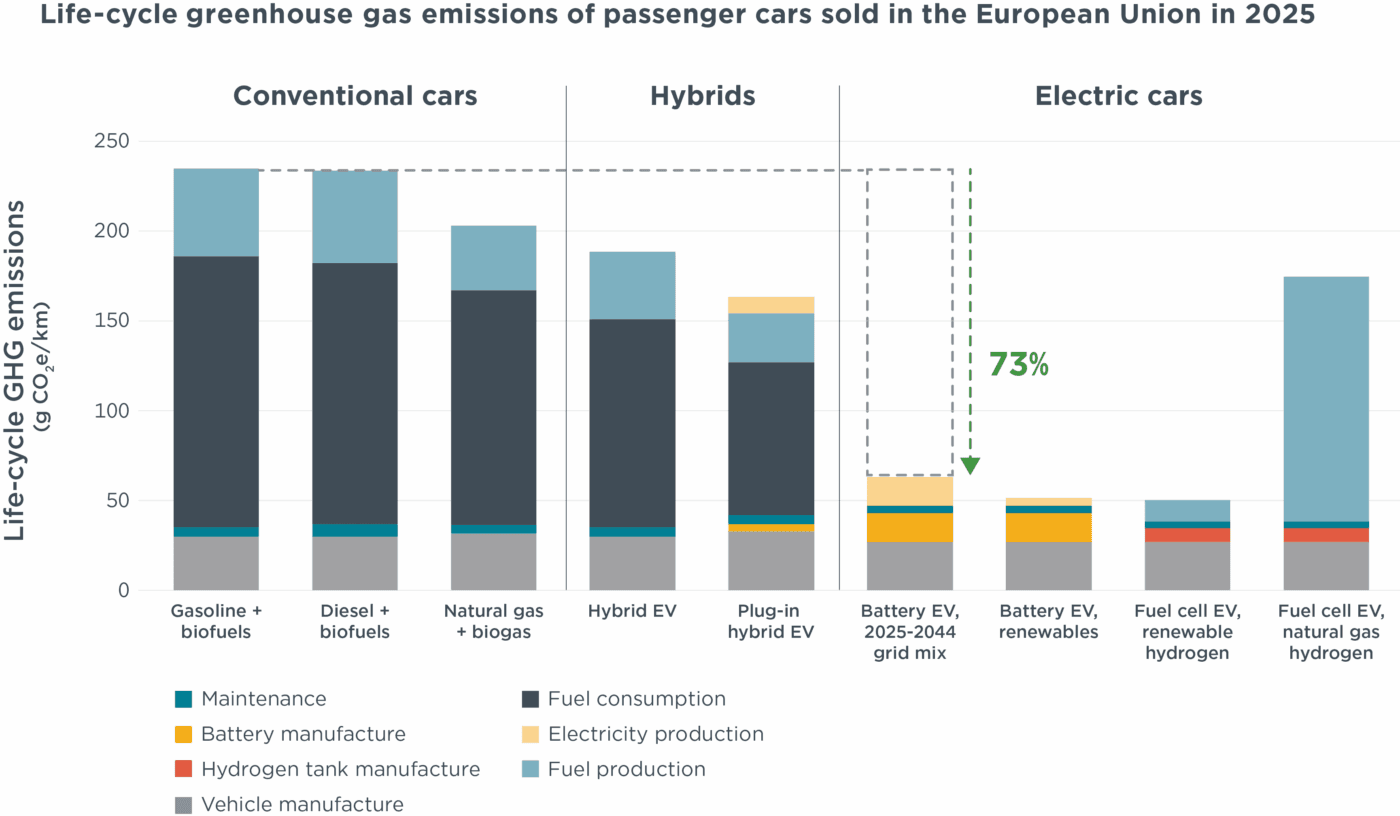

The main finding is that a fully electric car sold in Europe in 2025 emits 73 per cent less greenhouse gases over its lifetime than a petrol car (including production emissions). Compared to 2021, this represents an improvement of 24 percentage points in just four years. The reason: as Europe’s electricity mix becomes greener, so does the carbon footprint of EVs.

A cleaner power mix makes EVs cleaner

According to the ICCT, the study includes “greenhouse gas emissions from vehicle and battery production and recycling, fuel and electricity production, fuel consumption, and maintenance.” Real-world consumption data were used rather than official figures, which often distort reality, especially for plug-in hybrids. The methodology also considers the future development of the electricity mix over the vehicle’s lifetime, in this case up to 2044. By 2025, renewable energy is expected to cover 56 per cent of European electricity generation – up 18 percentage points from 2020. The EU’s Joint Research Centre predicts this share will reach 86 per cent by 2045.

However, the ICCT did not only look at fully electric cars. Other powertrains, such as hybrids and plug-in hybrids, show little or no progress in reducing their climate impact. This highlights one conclusion: only fully electric vehicles can achieve the emission reductions needed to meet climate targets in road transport. Thanks to the cleaner grid, the climate advantage of EVs has increased significantly in just four years, while hybrid emissions remain almost unchanged. Full hybrids produce around 20 per cent fewer emissions than petrol cars, and PHEVs around 30 per cent less. While hybridisation offers some savings, they fall far short of those achieved by pure EVs – and are insufficient to meet long-term climate goals, says the ICCT.

In numbers: petrol cars running on E10 emit an average of 235 grams of CO2-equivalent per kilometre over their lifecycle, diesels come in at 234 g/km, and gas-powered vehicles at 203 g/km. EVs charged on the EU grid emit just 63 g/km, or only 52 g/km when using renewable electricity. Hybrids cannot match these figures, coming in at 188 g/km (HEV) and 163 g/km (PHEV). Their largest emissions source remains fuel consumption. Even with greater use of biofuels, no significant improvement is expected for combustion or hybrid vehicles.

Battery chemistry relevant for CO2 emissions

“Battery electric cars in Europe are getting cleaner faster than we expected and outperform all other technologies, including hybrids and plug-in hybrids,” said Dr. Marta Negri, Researcher at the ICCT and co-author of the study. “This progress is largely due to the fast deployment of renewable electricity across the continent and the greater energy efficiency of battery electric cars.

The ICCT data also show that over a vehicle’s lifetime, propulsion energy remains the largest single factor for CO2 emissions, not production, nor battery manufacturing specifically, which often faces criticism. For battery production emissions, ICCT used the 2024 GREET model from Argonne National Laboratory, differentiating between LFP, NMC622, and NMC811 cells. Most BEVs and PHEVs sold in Europe use NMC622 cells, which served as the study’s baseline. If more LFP cells are used in future European BEVs, battery production emissions could decline further due to their lower footprint. NMC811 cells offer only marginal improvements over NMC622.

For NMC622, cell origin was also factored in, with weighted averages from Europe, the US, South Korea, Japan, and China: 72.8 kg CO2-equivalent per kWh. For a BEV with an average battery size of 53.4 kWh, this equates to 3.9 tonnes CO2 for battery production, while a PHEV with 13.3 kWh accounts for 1.0 tonne.

Although they play no meaningful market role in Europe, ICCT also assessed hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCEVs). The results are mixed: theoretically, FCEVs can cut emissions by up to 79 per cent compared to petrol cars – but only if powered by green hydrogen. However, nearly all hydrogen used in Europe is currently from fossil gas. “In contrast, fuel cell electric cars run on hydrogen produced from natural gas, which corresponds to almost the entirety of hydrogen available today, allowing only a 26% reduction of life-cycle emissions compared with gasoline cars”, the study states. Thus, FCEVs remain on par with hybrids in climate impact, despite their complex technology and infrastructure requirements.

Up to 79 per cent savings with fuel cells compared to ‘only’ 73 per cent for EVs? Not quite. The 79 per cent figure assumes purely renewable hydrogen, while the 73 per cent for BEVs uses the current EU electricity mix, which still includes coal and gas. Charged solely with renewables, BEVs reach the same life cycle CO2 levels as fuel cell vehicles powered by green hydrogen.

EVs quickly offset their ‘CO2 backpack’

Battery-powered EVs start with higher emissions due to production, the so-called CO2 backpack. For fuel cell cars, production of fibre-composite tanks also generates emissions (1.9 tonnes as per ICCT), but less than batteries.

However, FCEVs require significantly more renewable electricity overall due to hydrogen electrolysis losses. In total, both BEVs and FCEVs reach around 50 g/km life cycle emissions with 100 per cent renewables. For BEVs using the EU mix, this rises to about 70 g/km. By contrast, hydrogen from fossil gas yields roughly 175 g/km for FCEVs.

The ICCT warns against selective data usage, which has fuelled public confusion about EV climate impacts. “Misinformation and selective use of data have generated confusion regarding the climate credentials of electric vehicles,” the authors write. For example, while EV production causes roughly 40 per cent more emissions than petrol cars, this ‘CO2 backpack’ is offset after just 17,000 kilometres – typically within the first or second year of use. After that, the EV remains cleaner for the rest of its average 20-year life.

ICCT calls for fact-based debate

The ICCT also compares its findings to official figures, revealing that WLTP data understate combustion emissions by around ten per cent, while EV emissions would be 64 per cent (EU mix) or 26 per cent (renewables) higher if based on official data alone. Thus, the apparent “climate advantage” of EVs would be smaller. The ICCT emphasises its focus on realistic data to provide a more relevant assessment, detailing in its report how methodological choices influence outcomes.

“We hope this study brings clarity to the public conversation, so that policymakers and industry leaders can make informed decisions,” said Dr. Georg Bieker, ICCT Senior Researcher. “We’ve recently seen auto industry leaders misrepresenting the emissions math on hybrids. But life-cycle analysis is not a choose-your-own-adventure exercise. Our study accounts for the most representative use cases and is grounded in real-world data. Consumers deserve accurate, science-backed information.”

The report’s concluding policy recommendation is unambiguous: “The findings support the following policy considerations: The phaseout of new ICEV, HEV, and PHEV registrations by 2035 would align sector emissions with EU climate targets.”

0 Comments