BMW opens Battery Competence Centre in Munich

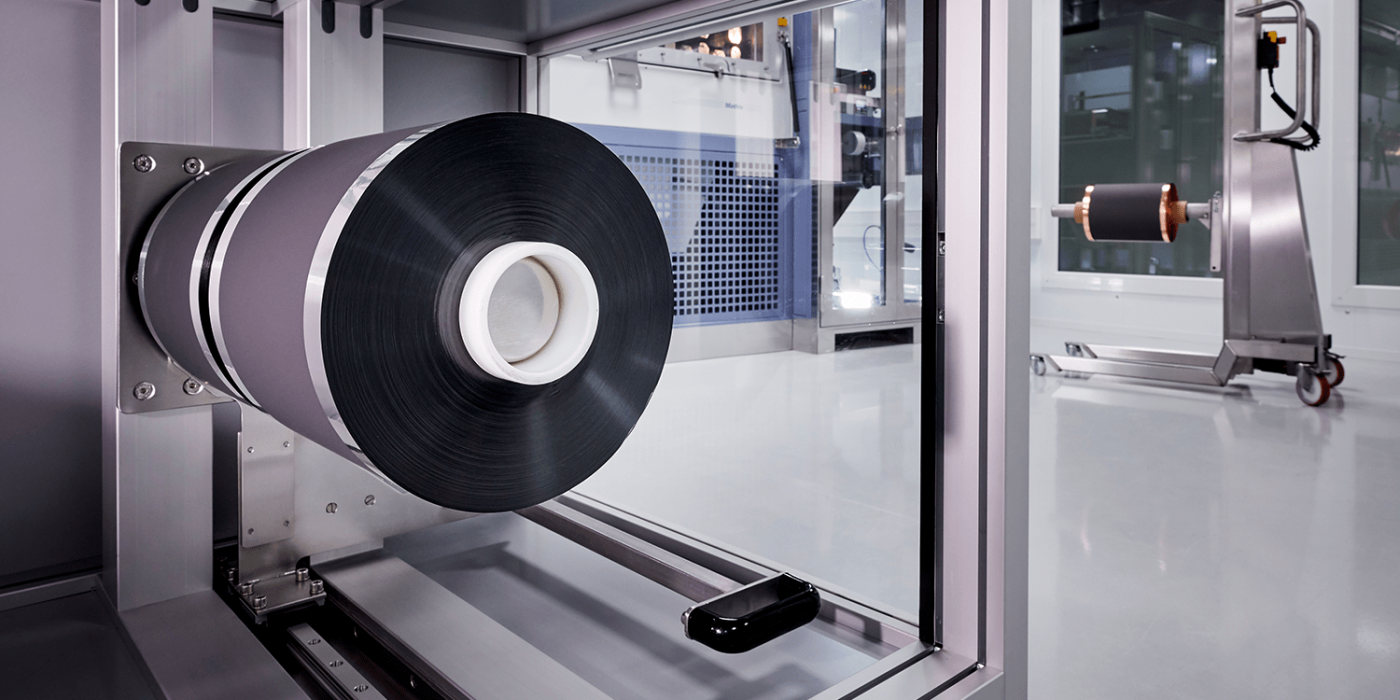

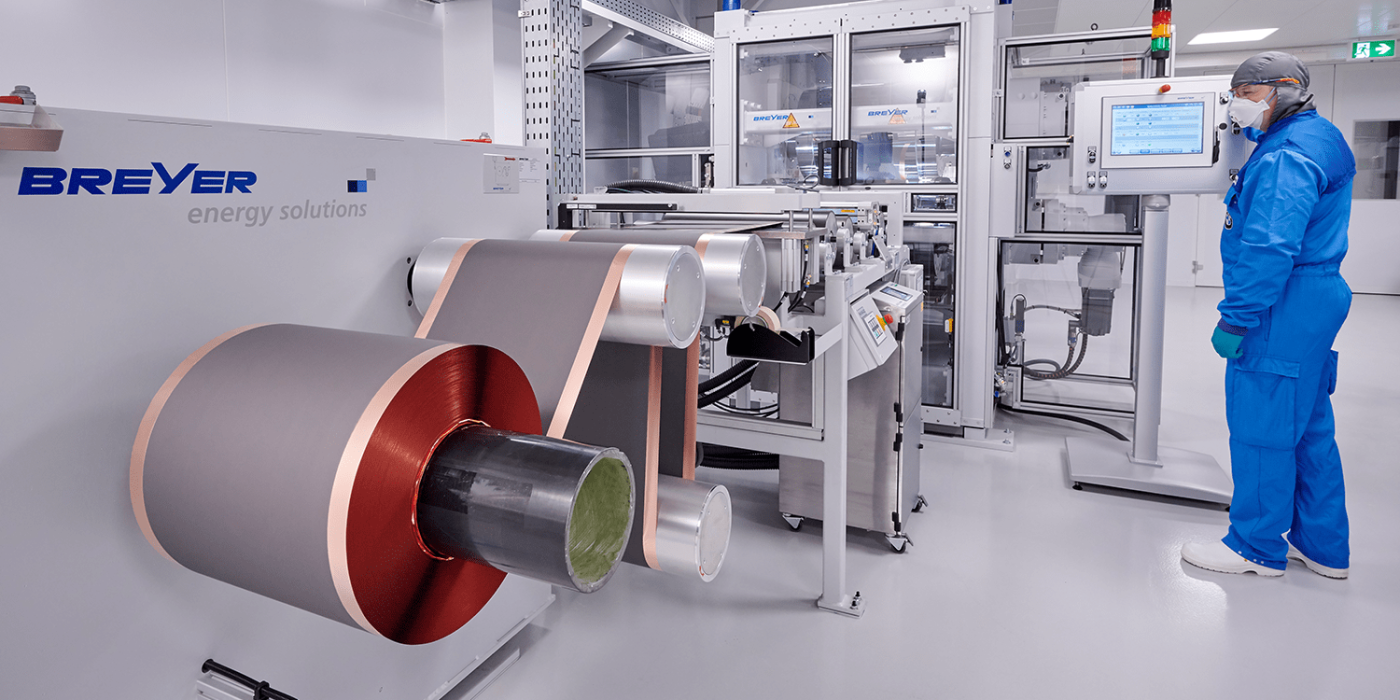

BMW has opened its new Battery Cell Competence Centre in Munich-Milbertshofen. The centre will develop new battery cells, manufacture them on a prototype scale and test them. The Munich-based company is still not planning for in-house series production.

The new building is about 12,000 square meters with about one third reserved for office space, the rest for laboratories and technical facilities. In the competence centre, BMW wants to be able to cover and analyse the entire spectrum of battery cells.

“In 2008, we set out to research battery cells,” says BMW CEO Oliver Zipse at the opening ceremony. “What you see today is not a start, but another milestone on the road to the future.”

According to BMW, it invested 200 million euros in the centre announced in 2017 – without public funding, Zipse emphasises. Around 200 developers are to develop the cells from scratch – from the purchase of materials to the preliminary products, from the most diverse cell types and formats to testing under extreme conditions. Previously, BMW had researched the cells a few kilometres away on Taunusstrasse in Munich. With the significantly larger new competence centre, BMW intends above all to increase the development speed, “which is currently very important in electromobility”, as BMW managers repeatedly stressed at the event.

Why all the effort when the big cell manufacturers such as CATL, Samsung SDI and LG Chem are also investing billions in cell research though? From BMW’s point of view, it is not only the battery cell that differentiates but also the system integration of the entire battery, including cooling. “We have entirely different possibilities than a cell manufacturer,” says Peter Lamp, Head of Cell Technology Development. “They often don’t understand what’s happening in the vehicle today because they lack experience in integration.”

One analogy BMW repeatedly refers to on this day is the baking of a cake. It doesn’t just depend on the exact quantities and quality of the ingredients, but also on how they are mixed, processed and baked – not every oven is the same. “It’s a very special technology, we need a lot of physicists and chemists,” says Zipse.

BMW didn’t buy off-the-shelf battery cells for the i3, but developed the technology and format itself and then worked with a supplier to ready it for series production. A business model BMW intends to maintain despite its modern competence centre. “It’s not important to produce the cell yourself,” says Zipse. “It’s essential to know what you want from the supplier.” The BMW Group has secured the forecast quantities for the long term through contracts.

However, BMW does not see any dependence on cell suppliers – Zipse refers to turbochargers for combustion engines, for example, which carmakers do not produce either. He expects an established market for automotive battery cells to develop in the coming years, as has happened with other components. In the long run, however, he does not want to rule out production: “If it should become necessary one day, we will be able to react”.

The Munich-based company hopes that its development will lead to greater flexibility in purchasing, as it is independent of the cell suppliers’ technology – words such as “at eye level” or “wanting to have a say in cutting-edge research” are used again and again.

Zipse appears unfazed by Tesla’s decision to establish its European Gigafactory, including battery production in Germany. “The competitor is an excellent example that it’s not just about a single technology, but the integration into a very complex system car,” says the BMW boss. “And we can do that very well in Germany.”

For a battery cell to be competitive, it must not only be safe, have a high energy density and last as long as possible, but come at the right cost as well – according to battery developer Lamp, the latter is a more significant challenge than higher energy density. “We can already foresee the increase in energy density over the coming years,” says Lamp. “In 2025, we can achieve ranges of 600 kilometres – with the same battery size and weight as today.”

In terms of cell costs, Lamp sees three key drivers: the exact materials used in future cell chemistry, the development of raw material markets, and developments in the market for battery cells. In the case of raw materials, in particular, he expects that the continually developing environment will lead to changes in the purchasing side due to the sharp rise in demand. According to BMW, this is a path it wants to follow – right down to individual mines. “We have to go down to the level of materials and raw materials to keep costs under control,” says Lamp.

And the transparency of raw materials. Zipse announces its intention to achieve “complete transparency”. One example: BMW wants to do without rare earth in its electric drives by switching to externally excited asynchronous motors from 2021.

For the fifth generation of electric car batteries at BMW, the Munich company wants to do without cobalt from the Congo. The company then buys material from mines in Morocco and Australia and makes it available to cell suppliers. In a few years, however, BMW plans to buy again in the Central African country. “We don’t want to exclude the Congo, it’s our declared goal to source in the Congo again,” says materials buyer Peter Zisch. “We believe that we will be able to do this again from 2025 onwards from selected mines”. BMW, BASF and Samsung SDI are already supporting similar projects in the Congo to establish clean and transparent cobalt mining there.

According to Zisch, the purchase of lithium in South America is also conceivable in the future. There are many mines BMW is in contact with, and some are very sustainable in their use of water and other raw materials.

It was precisely over these sustainable ways of thinking (or the lack of) though, Zipse received critic recently. The BMW boss had said in interviews that the customer would decide which car he wanted – and BMW would deliver. Zipse ignored the fact that a large SUV with a V8 petrol engine makes little sense in German city centres. Now he has changed the tone somewhat: “Sustainable mobility is a basic consensus in our society, and everyone must contribute here”, says Zipse. “The BMW Group is committed to the Paris Climate Agreement. This is what technological progress in the vehicle itself stands for; it does not happen outside the car.”

>> Sebastian Schaal reporting from Munich.

0 Comments